This end table by Richard Slosky demonstrates one way to attach a table top while allowing it to be able to expand and contract with changes in moisture content. Small L-shaped "buttons" are screwed to the bottom of the table top while an expanded slot on the inside of the table skirt accepts the leg of the button. As the top expands and contracts over time, it's able to move without putting stress on the table joinery or the table top - thereby letting this table last for many, many years.

First a word of caution. Here and in other publications precise numbers are calculated or given for different wood properties. These numbers are always based on some averages that have been developed in laboratory testing, sometimes over many years. Wood is a very complex material with many variables that will affect moisture content and wood movement. It is not possible to predict accurately the movement of a single piece of wood. The average of a quantity is much more predictable. Still the averages can be applied to most practical situations.For most of us it is adequate to know that a table top will move about .5 inches. It is inconsequential to calculate that it may move .457” or .514”. It is far more important to understand that it WILL move.

Wood expands and contracts with changes in the surrounding humidity and to a lesser degree the temperature. More humid air will cause wood to expand; drier air will cause wood to contract. This movement cannot be stopped. You can learn what to expect and techniques to cope with the movement.

Moisture content

Moisture content is expressed as a percentage and calculated as follows:

Moisture content = Weight of the water in the wood

Weight of the wood oven dry

In trees moisture content will range from 30% to more than 200%.

Water is present in wood as liquid or vapor inside the cells (free water) and water bound chemically to the cell walls (bound water). Visualize a hand full of straws or tubes. Water in the tubes is free but there is also water bound inside the walls of each tube.

The point at which the cell cavities are empty but the walls are still saturated with water is called the Fiber Saturation Point. In wood this averages about 28% but will vary by a few points depending on wood species, specific tree and even individual boards. As wood dries below this moisture content it shrinks until the moisture content reaches equilibrium with its surrounding environment.

Drying lumber, either naturally (air drying) or in a kiln is the process to lower the moisture content to the surrounding environment. For much of the United

States, the minimum moisture content of thoroughly air dried

lumber is 12% to 15%. Kiln dried hardwood will usually be less than 10%.

Dried lumber has many advantages over green lumber for Woodworkers. Removing excess water reduces weight, thus shipping and handling costs. Proper drying will help confine shrinking and swelling of wood in use to manageable levels. As wood dries, most of its strength properties increase. Properly dried lumber can be cut to precise

dimensions and machined more easily and efficiently; wood parts can be joined more securely or fastened together with nails, screws, bolts, and adhesives. Warping, splitting,

checking, and other harmful effects of uncontrolled drying are largely eliminated; and paint, varnish, and other finishes are more effectively applied and maintained.

The objective is to bring the moisture content of wood, as close as possible, to the level the finished product will experience in service. Acquire your lumber in advance and give it time to acclimate to the environment in which it will be used or worked. Sometimes it may be necessary to “stack and sticker” lumber to allow it to properly reach equilibrium with the environment.

Finished projects will continue to absorb or give off moisture with changes in humidity and temperature of the surrounding air. The wood will always undergo changes in moisture content and dimension. Consequently doors and drawers may stick during periods of high humidity. Moulding joints may open. Solid wood panels in raised panel doors may shrink exposing unfinished wood along the edges of the frame. Furniture moved from one part of the world to another may change enough in dimension that it must be reworked to function correctly. And, during a dry night a poorly designed furniture panel may explode with a bang!

Direction of Movement

Wood does not move in all directions equally. The greatest movement is across the grain. There is very little movement along the length.

Again a word of caution. We can predict, with a high degree of accuracy, the movement in a large quantity of wood. It is not possible to accurately predict the movement of a single piece of wood. Some of the variables to consider:

- Whether the piece is flat sawn or quarter sawn. More on this later.

- Sapwood content. Sapwood will usually change moisture content more rapidly than heartwood.

- Grain structure-open or closed pores.

- Defects in the wood.

- Changes in grain direction.

- Consistency of moisture content throughout the board. It is likely to have a higher moisture content in the center than on the surface.

- Tension in the wood.

- Location of the wood in the tree.

- Age of the Wood.

- Size of the piece

Wood technologists refer to flat sawn lumber as “tangential”. The saw blade cuts a kerf on a line tangent to the annual growth rings. Quarter sawn lumber is “radial”. The saw blade cuts a kerf from the pith across the annual growth rings. Lumber is seldom completely tangential or radial but ever changing throughput the cutting process. Look at the end of a board; if the angle of the rings to the face is 0 to 30 degrees the board is flat sawn; if the angle is 60 to 90 degrees the board is quarter sawn. In between, 30 to 60 degrees, is bastard or rift sawn. Flat sawn lumber has tapered cathedral grain, while quarter sawn lumber has long straight grain lines.

|

Some species-White Oak, Lacewood, Sycamore etc.- have large rays that are exposed when quarter sawn producing a dramatic pattern. Similarly, woods with interlocked grain-Sapele, African Mahogany etc. - produce a striped ribbon effect when quarter sawn.

|

Movement across the grain is greatly influenced by how a board was sawn. On average flat sawn hardwood will shrink 8% from the Fiber Saturation Point to oven dry while quarter sawn hardwood will shrink only 4%. There are tables for tangential and radial shrinkage by species but for most applications knowing that quarter sawn lumber moves only half as much as flat sawn is sufficient.

On some projects the orientation of the cut will make a difference but for most applications either flat sawn or quarter sawn is satisfactory. Here are some characteristics of each:

| Flat sawn | Quarter sawn |

Shrinks and swells less in thickness |

Shrinks and swells less in width |

Grain presents a cathedral pattern. Figure patterns resulting from annual rings and are displayed more conspicuously |

Grain presents a pattern of long straight lines. Raised grain caused by separation in annual rings is not as pronounced. |

Knots are round or oval; boards with round or oval knots are stronger than boards with spike knots |

Knots are spike shaped; boards with spiked knots are weaker than boards with round or oval knots |

Is less susceptible to collapse in drying |

Cups, surface-checks, and splits less in seasoning and in use |

Shakes and pitch pockets, when present, extend through fewer boards |

Does not allow liquids to pass through readily in some species |

|

Holds paint better in some species |

Standard sawing pattern for most species. Generally available |

Commercially sawn in only a few species. May be difficult to obtain |

Less costly |

More costly |

Coping with Wood Movement

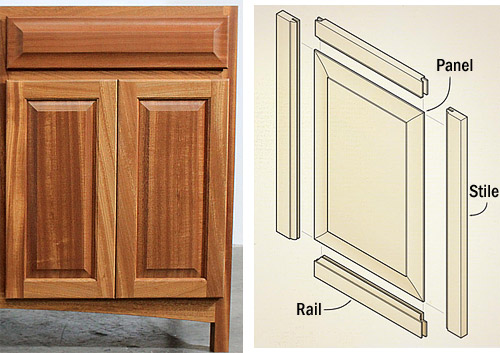

These cabinet doors show an example of frame and panel construction, one method of dealing with wood movement in solid-wood furniture. The doors consists of a frame made of rails and stiles, and then there's a solid wood panel that's attached to the frame in a hidden groove. The panel is not glued in place, it simply floats within the frame. This method allows the overall door to stay the same size over the years while allowing the panel to expand and contract as needed.

Take wood movement into account in the design of your project. Experience taught woodworkers long ago how to deal with dimensional change due to change in moisture content. The answer was joinery that allowed for wood movement. Despite today’s super-strong adhesives and moisture fighting finishes that is still the solution.

Here are some techniques.

Acquire your lumber in advance and give it time to acclimate to the environment in which it will be used or worked. It may be necessary to “stack and sticker” lumber to allow it to properly reach equilibrium with the environment before it is used.

Consider plywood. Plywood is stable; it does not expand and contract like solid wood. Many hardwood species are available or sheets can be made using veneer. Flexible paper back veneer is easy to work with and readily available. Cabinets and furniture cases are good candidates for plywood construction.

Plan the joinery to avoid cross-grain assemblies. Cross-grain joints constantly pull in different directions weakening the joint over time. Design joints so the grain runs in the same direction on both pieces.

Allow tops to move freely. Attach tops with Figure 8 Connectors, Z clips, shop made blocks or elongated screw holes. All of these methods will securely attach the top but all it to move across its width. A 36” wide top, made with flat sawn lumber, can move more than an inch with a 10% change in moisture content.

Use the nickel-dime approach. When fitting cabinet doors or drawers build to the normal humidity in your area. During periods of low humidity allow a reveal the width of a nickel. Conversely, during periods of high humidity allow for a dime reveal.

Use a sliding dovetail to apply moulding across the grain. Glue only the first 2-3” allowing the rest of the moulding piece to move.

Use elongated holes for screws. When attaching A cross-grain board glue and screw the front few inches but secure the remaining length with screw in slots. This will allow the back to move but keep the front firmly aligned.

Use “frame and panel” construction. Panels may be plywood or solid wood with a raised center field. Most folks like the look of raised panels better. If using solid wood panels, DO NOT glue it to the frame. The panel must be free to float and change dimension. A small spot of glue in the center of the width will keep the panel centered.

Apply a finish. Apply an equal number of coats to ALL surfaces to equalize the loss or gain of moisture. No finish will block moisture transfer; they just slow it down. Penetrating oils provide the least protection. Epoxy offers the greatest.

The tendency of wood to contract and expand, shrink and swell cannot be stopped. You must plan for it. Design and build with dimensional change in mind.